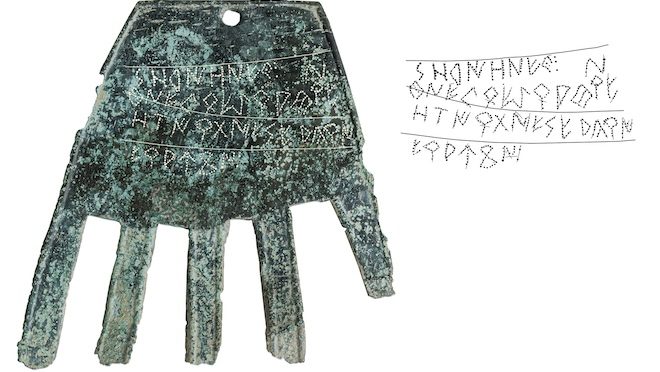

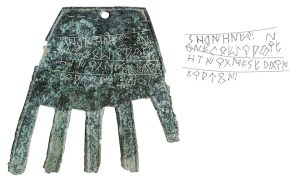

The origins of the Basque language are lost to time, or so we are told. However, new discoveries such as the Hand of Irulegi challenge some of those assumptions and reveal new and exciting insight. At the same time, researchers continue to chip away, examining the body of evidence to further our understanding of the origins of the language and its possible connection to other languages. As a consequence, old theories such as the relationship between Basque and Iberian are getting a new look.

- The central tenant of the Basque-Iberian hypothesis is that the various tribes that inhabited the Iberian peninsula before the arrival of the Romans spoke a language or collection of languages that were related to Basque. When the Romans came, most of those tribes became latinized and the only remnant of that family of languages is Basque.

- This theory had its heyday between the 1500s and 1700s. The basis for the original theory was from the historian Flavius Josephus (1st century AD), who said that Tubal, grandson of Noah, founded the people of the “Tubeli, who are now called Iberians.”

- With time, the Basque-Iberian theory lost favor, as modern Basque is of little help in deciphering the few Iberian texts that have survived to present day. Further, Basque-Iberian advocates pushed their ideas too far, to suggest that many Italian place names could be interpreted this way, for example. And, as with all things Basque, politics inserted itself. People argued that there was no way that Basque was an indigenous language to the peninsula, attacking the historical basis of the language as a way to undermine the fueros. However, perhaps the biggest problem with the Basque-Iberian theory is that, while some words seem recognizable from a Basque perspective, the overall meaning of the texts is undecipherable, meaning we can’t use Basque to understand those texts.

- On the other hand, there is evidence that suggests the languages are linked. There are names that are similar in the two languages, for example Araxes/Araiza and Ararat/Aralar. And there are non-linguistic traits that suggest a connection, including that both cultures used horned headdresses. The theory regained respect when scholar of the Basque language Wilhelm von Humboldt argued that Iberian place-names could be divided into two families: one with a Celtic origin and another that “follows the phonetic system of the Basque language.”

- More recently, researchers like Eduardo Orduña Aznar and Joan Ferrer I Jané have delved further into the relationship between Basque and Iberian. They have found that, for example, the number systems are very similar (here the Iberian word is in bold and the Basque word in italics): ban bat (one), bi bi (two), laur lau (four), borste bost (five), okrei hogei (twenty), orkeiborste hogei ta bost (twenty-five). As the last example demonstrates, the two languages seem to compose larger numbers in a similar way.

- Orduña has expanded his analysis to consider kinship terms. For example, he finds possible connections ata aita (father), uni(n) unide (wet nurse), -kidei -(k)ide (companion), amongst others. Beyond word similarities, he argues the two grammars are related. Both use the suffix -en to denote possession. Finally, there is a word on the Hand of Irulegi that says efaukon, which is similar to an archaic Basque word meaning “he/she gave.”

- Orduña is careful to say that his analysis is no proof that the two languages are linked. However, he concludes that there are enough similarities and evidence to suggest a link and that warrants further research.

A full list of all of Buber’s Basque Facts of the Week can be found in the Archive.

Primary sources: Estornés Zubizarreta, Idoia. VASCO-IBERISMO. Auñamendi Encyclopedia. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/vasco-iberismo/ar-130027/; New Connections Discovered Between the Ancient Iberian Language and Basque, Beyond Numbers by Guillermo Carvajal, La Brújula Verde; One of Europe’s Most Mysterious Languages May Share Ancient Roots with Iberian by Oguz Kayra, Arkeonews